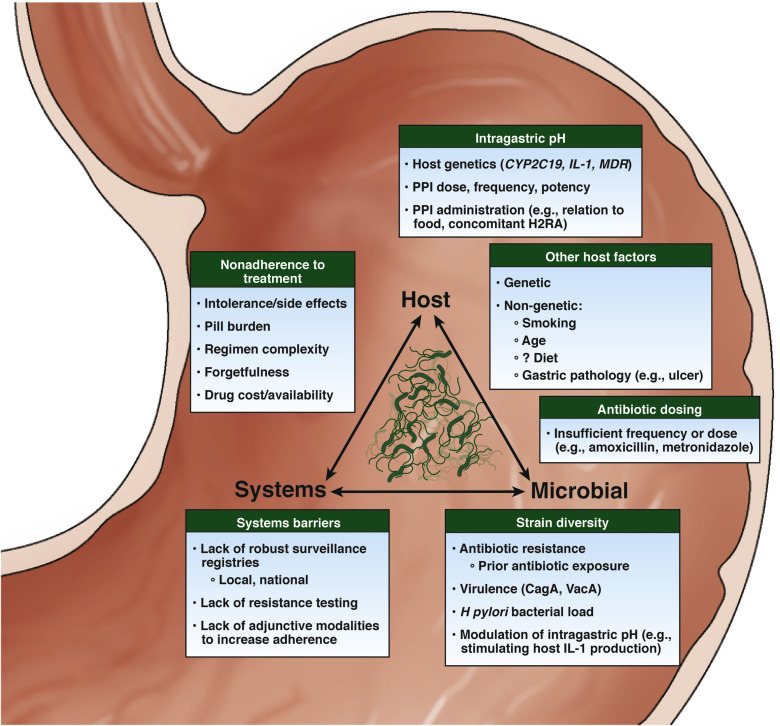

1. The usual cause of refractory H. pylori infection (persistent infection after attempting eradication therapy) is antibiotic resistance. Providers should attempt to identify other contributing etiologies, including inadequate adherence to therapy and insufficient gastric acid suppression.

2. Providers should conduct a thorough review of prior antibiotic exposures. If there is a history of any treatment with macrolides or fluoroquinolones, then clarithromycin- or levofloxacin-based regimens, respectively, should be avoided given the high likelihood of resistance. By contrast, resistance to amoxicillin, tetracycline and rifabutin is rare, and these can be considered for subsequent therapies in refractory H. pylori infection.

3. Eradication regimens for H. pylori are complex and might not be fully comprehended by patients. Barriers to adherence should be explored and addressed prior to prescribing therapy. Providers should explain the rationale for therapy, dosing instructions, expected adverse events and the importance of completing the full therapeutic course.

4. If bismuth quadruple therapy failed as a first-line treatment, shared decision making between providers and patients should guide selection between (a) levofloxacin- or rifabutin-based triple-therapy regimens with high-dose dual proton pump inhibitor (PPI) and amoxicillin, and (b) an alternative bismuth-containing quadruple therapy, as second-line options.

5. When using metronidazole-containing regimens, providers should consider adequate dosing of metronidazole (1.5-2 g daily in divided doses) with concomitant bismuth therapy, because this may improve eradication success rates irrespective of observed in vitro metronidazole resistance.

6. In the absence of a history of anaphylaxis, penicillin allergy testing should be considered in a patient labeled as having this allergy in order to delist penicillin as an allergy and potentially enable its use. Amoxicillin should be used at a daily dose of at least 2 g divided 3 times per day or 4 times per day to avoid low trough levels.

7. Inadequate acid suppression is associated with H. pylori eradication failure. The use of high-dose and more potent PPIs, PPIs not metabolized by CYP2C19, or potassium-competitive acid blockers, if available, should be considered in cases of refractory H. pylori infection.

8. Longer treatment durations provide higher eradication success rates compared with shorter durations (eg, 14 days vs 7 days). Whenever appropriate, longer treatment durations should be selected for treating refractory H. pylori infection.

9. In some cases, there should be shared decision making regarding ongoing attempts to eradicate H. pylori. The potential benefits of H. pylori eradication should be weighed carefully against the likelihood of adverse effects and inconvenience of repeated exposure to antibiotics and high-dose acid suppression, particularly in vulnerable populations, such as the elderly.

10. After two failed therapies with confirmed patient adherence, H. pylori susceptibility testing should be considered to guide the selection of subsequent regimens.

11. Compiling local data on H. pylori eradication success rates for each regimen, along with patient demographic and clinical factors (including prior non-H. pylori antibiotic exposure) is important. Aggregated data should be made publicly available to guide local selection of H. pylori eradication therapy.

12. Proposed adjunctive therapies, including probiotics, are of unproven benefit as treatment for refractory H. pylori infection, and thus, their use should be considered experimental.