Diagnosis

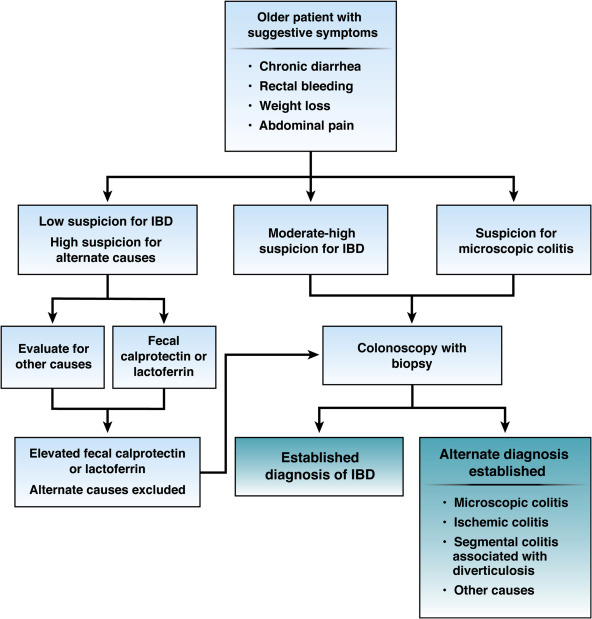

1. A diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis) should be considered in older patients who present with diarrhea, rectal bleeding, urgency, abdominal pain or weight loss because up to 15% of new diagnoses of IBD occur in individuals older than 60 years.

2. Fecal calprotectin or lactoferrin may help prioritize patients with a low probability of IBD for endoscopic evaluation. Individuals presenting with hematochezia or chronic diarrhea with intermediate to high suspicion for underlying IBD, microscopic colitis or colorectal neoplasia should undergo colonoscopy.

3. In elderly patients with segmental left-sided colitis in the setting of diverticulosis, consider a diagnosis of segmental colitis associated with diverticulosis in addition to the possibility of Crohn’s disease or IBD-unclassified.

Treatment: general principals

1. A comprehensive initial assessment of the older patient is important to collaboratively establish short- and long-term treatment goals and priorities.

2. Clinicians should risk-stratify patients based on the likelihood of severe clinical course, including assessment of perianal or penetrating phenotype, long-segment small bowel involvement (Crohn’s disease), extensive colitis (ulcerative colitis), anemia, hypoalbuminemia, elevated inflammatory markers and weight loss, to determine an appropriate therapeutic strategy.

3. Systemic corticosteroids are not indicated for maintenance therapy. When used for induction therapy, when possible, clinicians should prefer nonsystemic corticosteroids (like budesonide) or even early biological therapy initiation if budesonide is not appropriate for the phenotype of the disease being treated.

4. Candidacy for immunosuppression should be based on chronologic age, as well as consideration for the patient’s functional status, comorbidities including prior neoplasia and potential for infectious complications, and frailty.

5. When possible, immunomodulatory treatments with lower overall infection or malignancy risk (vedolizumab, ustekinumab) may be preferred in older patients. However, choice of treatment must also include assessment of clinical context, efficacy of treatments for specific phenotypes, rapidity of onset of action and ability to achieve corticosteroid-free remission.

6. Consideration of thiopurine monotherapy for maintenance of remission in older patients should balance the convenience of its oral route of administration and lower cost with relatively lower efficacy, slow onset of action and an increase in risk of nonmelanoma skin cancers and lymphoma in this population.

7. Older patients with IBD have a greater burden of comorbidity than younger patients. Optimization of comorbidity is important to minimize the risks associated with IBD and its treatment and guide selection of the appropriate agent.

8. The decision about the timing and type of surgery in older patients with IBD should incorporate disease severity, impact on functional status and independence, risks and effectiveness of medical therapy, candidacy for surgery, and risk of postoperative complications.

9. The increased risk of fracture, venous thromboembolism, infections including pneumonia, opportunistic infections, and herpes zoster and risk of skin and nonskin cancers (including lymphoma) should be incorporated in therapeutic decisions.

10. Care for the older patient with IBD should be multidisciplinary, actively engaging gastrointestinal specialists, primary care providers (including geriatricians), other medical subspecialists (eg, cardiologists) mental health professionals, general or colorectal surgeons, nutritionists, and pharmacists. Engaging with family and caregivers may also be appropriate in formulating a plan.

Health maintenance

1. Clinicians should facilitate adherence to vaccination schedules, including influenza, pneumococcal and herpes zoster vaccines, in older patients with IBD. If possible, vaccination should be scheduled before starting immunosuppression.

2. The decision to continue or stop colorectal cancer surveillance in older patients with long-standing ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s colitis should be made incorporating age, comorbidity, overall life expectancy, likelihood of endoscopic resectability of the lesion, and candidacy for colon resection surgery.